Best White Chocolate in the World

This article explores the origins and history of chocolate, tracing cacao’s use and cultural significance among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. It

News > Fair Trade Chocolate Labels Unwrapped and Explained

Fair Trade chocolate, celebrated for its promise of equitable sourcing, paradoxically offers farmers a mere 20% premium over market prices. This raises a poignant question: In a landscape where cacao cultivators predominantly grapple with destitution, why does this modest increment persist as the pinnacle of our efforts?

Research consistently indicates that “most consumers are willing to pay more for certified products than for those without certification, and among certifications.” This forms the basis of the fair trade ecosystem of certifications, whereby consumers are willing to pay a higher price to benefit small farmers, so in turn chocolate makers are willing to pay a higher price for Fair Trade certified beans, which in turn incentivizes bean producers to comply with certain standards and pay a small amount for the auditing structure necessary to maintain the integrity of various Fair Trade organizational labeling schemes. Here, we embark on an exploration into complex concerns that envelop the domain of fair trade chocolate. Amid the kaleidoscope of labels that embellish chocolate packaging, not all certifications are equal. This article navigates the multifaceted expanse of fair trade chocolate, breaks down the differences between the diverse array of distinct “Fair Trade” designations that span the global chocolate market.

Our international chocolate awards pay tribute to the obsessive, passionate individuals striving for chocolate perfection around the world. We honor renowned European chocolate houses who have perfected their bonbon and truffle recipes for generations alongside emerging bean-to-bar chocolate makers experimenting with bold ingredients like black currant and elderflower. During our blind tastings, we judge each craft chocolate bar and bonbon on its flavor, aroma, textures and craftsmanship to identify the best chocolate in the world.

See the winners +

Critics have long aimed their arrows at the Fair Trade model. Studies show that bean-to-bar and craft chocolate makers have three primary criticisms of the labeling scheme: “the cost of label adoption is too high relative to its efficacy; certifiers’ enactment of professed values is fundamentally flawed; and many labeling schemes have become commercialized and watered-down.” But perhaps the most resounding critique revolves around its approach to income. While the promise of a minimum price for cocoa may seem like a safeguard, the unsettling truth remains—the minimum is still tethered to the unpredictable ebbs and flows of the global cocoa market. This oscillating reality creates an unstable economic outlook for farmers with little to no savings, usually in countries where governments do not have the financial power to cushion their farmers from low prices like most big, rich countries do for their own farmers. This has left many skeptical of Fair Trade’s efficacy.

Compounding these concerns is the alarming decline in cocoa bean prices witnessed over the past two decades. Even within the protective embrace of Fair Trade, cocoa prices have at times failed to ensure a more than a bare subsistence livelihood. This struggle is amplified by the labor-intensive nature of cocoa bean production, a facet that balloons production costs for farmers. It’s a disheartening equation where farmers invest consistent resources into their crops, only to witness buyers chiseling down the offered price year after year. The paradox is stark: while consumers continue to pay a stable price for their beloved chocolate bars, the compensation for the very source of that delight dances on the capricious winds of the market.

Few consumer commodities purchases other than gas are subject to the daily market fluctuations. Consider for a moment the chaos that would ensue if every purchase, from a chocolate bar to a new pair of jeans, hinged on the fleeting market price of the day. The practicality of such a scenario crumbles upon scrutiny. Consumers have the privilege of paying a relatively consistent amount for their daily purchases, yet the very farmers responsible for cultivating those pleasures are subjected to a mercurial spot-market compensation regime. The incongruity is evident, sparking questions on why stability is a currency that seems more readily available to some than others.

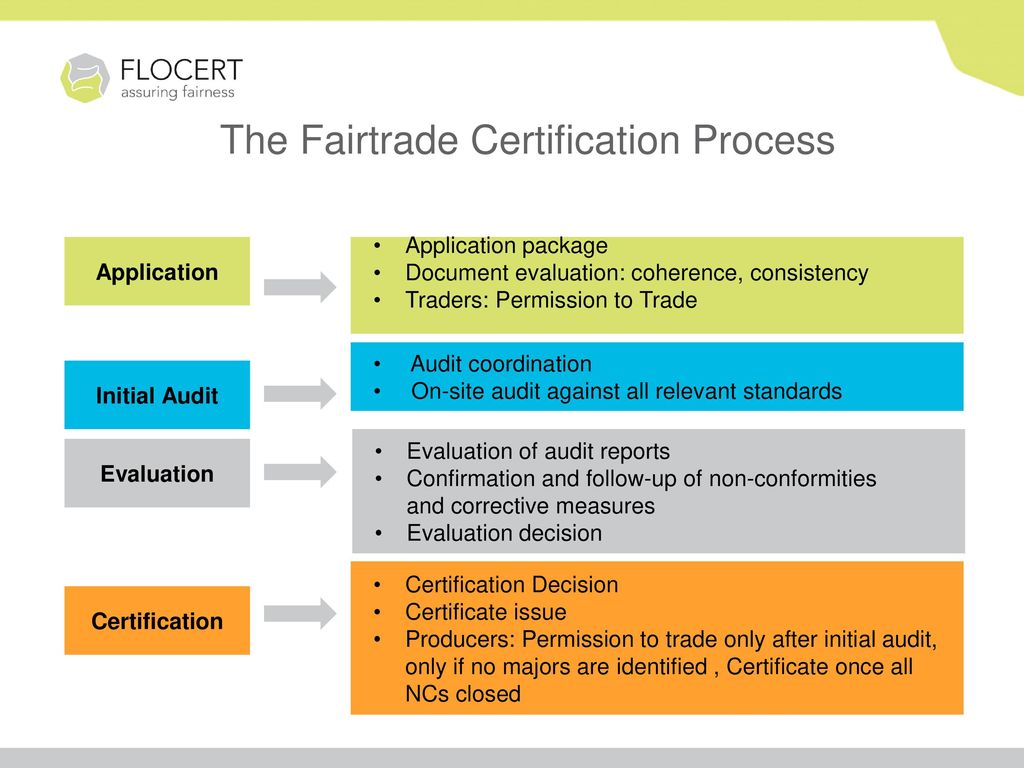

The maintenance costs of the independent Fairtrade Labeling Organization International (FLO) and its auditing counterpart, FLOCERT, have prompted two major consequences in the past few years. Initially, we’ve witnessed the withdrawal of major chocolate corporations, once Fairtrade allies, opting to forge their own “fair” labels. Consequently, many major global “Fair Trade” chocolate brands have pivoted to embrace these alternative insignias.

In parallel, a cohort of ethical trade proponents questions FLO’s overall efficacy, gravitating towards alternate models like direct trade. These advocates perceive the current impact of Fair Trade as lackluster. This dual trajectory poses a formidable challenge to the movement, as its enduring influence hinges upon the bedrock of consumer familiarity nurtured over decades.

Despite its gradual expansion, Fair Trade’s slice of the sprawling global cacao trade remains marginal in the context of the mass market. The emergence of rival ethical trade initiatives is further eroding its market share, amplifying the pressure. Should Fair Trade falter against the juggernaut of established chocolate conglomerates and artisanal producers, its growth prospects stand jeopardized.

This conundrum embodies a paradox, a Catch-22 of sorts. Such a setback would paradoxically underscore the limitations of Fair Trade’s current impact, inadvertently reinforcing the competitive narratives espoused by rival initiatives, as we will delve into below.

The set of stipulations established by FLO, specifically the mandate that farmers organize into cooperatives to access program benefits, has been criticized as a form of exclusivity and an administrative hurdle imposed on small-scale farmers (for reference, the June 2023 update to the Small Producer Organisations Compliance Criteria runs to 213 pages of checklists).

Yet, these tradeoffs are not without their reasons or intricacies. Disparities in influence, voice, knowledge, and resources persist even among cooperative members. As highlighted in the 2012 study by Davenport & Low, Fair Trade’s application of the term “producer” adds to the complexity of untangling the entities involved in the model’s supply chain and their actual gains from transactions.

The vagueness of certain terminology raises the concern that fair trade efforts might merely replace one intermediary with another. For instance, Fairtrade standards guarantee that the ingredients within a product are Fairtrade-certified up to a specified quantity. However, producers under certification are not bound to exclusively sell Fairtrade materials.

According to FLOCERT’s compliance checklist, a minimum of 50% of the supply should meet Fairtrade criteria. There are reasons for this. Supply chains are global and complex, mixing is common, and even when a genuine effort is made, craft chocolate makers often want to mix bean origins to get the flavor profile they want, and not every origin has a steady supply of FLO-certified beans. All of this means that some producer organizations engage in markets beyond the realm of Fairtrade, and it is not unheard of for producers to purchase a 51/49 mix for FLO-certified beans to minimize the extra expense of fair trade chocolate, while maintaining the consumer halo of the Fairtrade logo.

Doubts persist regarding the efficacy of Fair Trade endeavors in overseeing and enforcing adherence to regulations as well as the appropriate utilization of funds. Within this realm lie pressing concerns such as the employment of minors and refugees, raising questions about Fair Trade’s capacity to maintain vigilance. One of the central areas of focus has been the issue of child labor—a subject over which Fair Trade has maintained stringent standards. However, a nuanced distinction has been drawn between coerced child labor and instances where children contribute to their families’ agricultural activities as circumstances demand. In most cocoa-bean producing areas of the world including West Africa where the vast majority of beans worldwide are grown, children working on family farms are the near-universal norm as it has been throughout history and across almost every agricultural culture in the world.

The intricate interplay of labor-intensive cocoa production and deeply ingrained cultural norms underpins the challenge of entirely eradicating child labor. Navigating these intricacies, audit agents predominantly engage with cooperatives, drawing insights from their archives and conducting on-site appraisals to ascertain compliance.

Complications arise in instances where meticulous record-keeping has faltered, a predicament that agents are left powerless to rectify. Detractors have further raised questions about the allocation of Fair Trade premiums and the feasibility of tracing transactions. Skepticism lingers over the adequacy of human resources available for conducting comprehensive audits, a pertinent concern as producer organizations may encompass vast networks of thousands of farmers.

Concerns also surface regarding the market dynamics influenced by labeling endeavors. Critics argue that the assured Fairtrade Minimum Price might disincentivize producers from enhancing cocoa bean quality. The anticipation is that inferior cocoa beans could eventually compete against superior alternatives, although this scenario has yet to materialize.

In the realm of Fairtrade, composite products such as chocolate are characterized by their multi-component nature. The primary Fair Trade label alone does not reveal whether the chocolate bar is entirely of fairly traded components, or is a 51/49 mix. Fairtrade employs a Mass Balance mechanism that permits certification of ‘composite products,’ denoting those not exclusively reliant on fair trade-certified ingredients.

In accordance with a 2020 global strategy aimed at broadening farmers’ global market access, Fairtrade revised its policy to enable enterprises to adopt an “ingredient label” for multi-component products sourced from a single Fairtrade-certified ingredient. This initiative, previously identified as the Fairtrade Sourcing Program, underwent subsequent expansion. While the strategy facilitates farmers in extending their market reach, it might obfuscate the ultimate origin of the end product.

Consumers eager to unravel the intricacies of their chocolate bars’ contents must acquaint themselves with labeling directives. Dedicated aficionados and professionals may take this extra step, but the average consumer- even one interested in supporting the broad concept of “fair trade” won’t, and relies on simplified labeling donating the “ethically” sourced chocolate from the “unethically” sourced beans.

Within the intricate web of the Fair Trade movement, a mosaic of initiatives with slightly different emphases designed to address the perceived shortcoming of other labeling schemes all brandishing their own distinct labels. Yet, this landscape isn’t immune to exploitation. Applying for certification costs money (which in theory will be more than recouped by the higher sale price of certified beans), but as with any system some profit-minded entities have attempted to cash in on the trend, affixing these labels to products that fall short of global benchmarks.

Fortunately, a beacon shines amid this complexity. The Fair World Project has meticulously crafted a comprehensive compendium – a 124-page manual – elucidating the realm of Fair Trade Labels. This guide meticulously catalogs prominent Fair Trade organizations and provides a neutral assessment and ratings for enhanced clarity. Below are the relevant labeling schemes for chocolate which spotlights most of the ubiquitous labels peppering your local craft chocolate scene.

Fairtrade International is the oldest and most widely recognized global fair trade certification. It focuses specifically on empowerment of small producer organizations in developing countries through fair pricing, premiums, pre-financing, and capacity building. Fairtrade has robust standards for democratic governance and marginalized producer inclusion. It also conducts extensive awareness-raising and advocacy activities to transform global trade. However, Fairtrade does allow product-specific exceptions for plantations and contract production. Its standards development is guided by robust policies for stakeholder engagement and power balancing between producers and companies.

Fair Trade USA broke away from Fairtrade International in 2011 in order to expand certification beyond small farmers' cooperatives. They certify large farms, plantations, and factories and require only 20% fair trade content for use of their label. Fair Trade USA's standards lack robust requirements related to fair pricing, pre-financing, and producer empowerment. They also conduct limited advocacy on trade justice. Their standards development process favors corporate participation over small producers. However, Fair Trade USA does aim to benefit farmworkers on plantations in addition to small farmers.

Fair for Life is an international certification run by Ecocert that takes a universal approach to fair trade, certifying producer groups in both developing and developed countries. It combines criteria on fair trade, social responsibility, and environmental sustainability. Fair for Life recognizes several other fair trade certifications as equivalent and allows blending of fair trade and conventional ingredients. A key distinguishing factor is its acceptance of various models like contract production and plantations in addition to smallholder cooperatives. Fair for Life conducts limited advocacy or awareness-raising around fair trade issues. Its standards development process involves some producer participation but is not fully inclusive of all stakeholders.

The Small Producers' Symbol was created and is governed by small producer organizations affiliated with CLAC (the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Fair Trade Small Producers). It only certifies producer cooperatives and associations, excluding plantations and contract production models. SPP has very detailed requirements and strong auditing procedures. It sets minimum prices higher than other labels for many products. SPP focuses on producer empowerment and supply chain transparency rather than extensive awareness-raising or advocacy.

Rainforest Alliance and UTZ (the organizations merged in 2018) standards emphasize sustainable agricultural practices, animal welfare, ecosystem conservation, and environmental protection at the farm level. However, they lack detailed requirements for fair pricing, long-term trade relationships, pre-financing of crops, and democratic producer organizations that define fair trade certification. The focus is verifying farm-level practices rather than supply chain transparency or empowerment of producer groups.

The World Fair Trade Organization is a global network of fair trade enterprises dedicated fully to fair trade principles and practices. Their Guarantee System certifies entire fair trade organizations rather than specific supply chains. Only members who undergo monitoring audits can use the WFTO product label, placed alongside their organization name. WFTO does not allow the label directly on products from uncertified supply chains. It conducts extensive advocacy and awareness-raising around fair trade issues and principles. WFTO's governance structure is member-based without outside corporate participation.

Biopartenaire is a French association that originally created two separate labels - one for fair trade partnerships with producers in developing countries and one for local partnerships within France. In 2015, these two labels merged into a single Biopartenaire ("Organic Partner") label that can certify supply chains involving both Southern and Northern producers. A key focus of Biopartenaire is building long-term supply chain partnerships between French organic companies and producers. It requires organic certification for all products. Biopartenaire has detailed fair trade criteria related to fair pricing, premiums, pre-financing, and capacity building. However, it does not conduct extensive advocacy or awareness-raising activities. Its standards development is focused on the partnerships between French companies and producers rather than empowerment of marginalized producer groups.

Cocoa Life is Mondelēz International’s internal sustainability program for its cocoa supply chain. Mondelēz is the mega-brand which sold 13% of all global chocolate products in 2023 and owns international brands including Cadbury, Milka, Toblerone, and Côte d'Or. Mondelēz’s Cocoa Life certification primarily focuses on community development projects in cocoa growing areas rather than binding requirements for suppliers related to fair pricing (which would cost Mondelēz more to adhere to), premiums, or good governance. Cocoa Life conducts training and capacity building for farmers as well as investments in access to education and nutrition. Compliance is verified through third-party audits by SCS Global Services. However, unlike fair trade certifications, detailed standards documents are not disclosed publicly. This means claims about empowering farmers economically cannot be fully evaluated.

The Nestlé Cocoa Plan aims to improve the productivity and quality of cocoa production, providing training and planting materials to farmers. Nestlé’s array of candy brands including KitKat, Aero, Crunch, and faux-craft chocolate brand l'Atelier make it the sith largest cocoa purchaser in the world. However, Nestlé’s in-house Cocoa Plan certification does not have the same robust standards for fair pricing, premiums, and long-term commitments that are typical of fair trade certification. The program focuses more on agronomy for higher yields than on farmer incomes and empowerment. Compliance and impact are self-reported by Nestlé in their sustainability reports, without independent audits against published standards as found in fair trade.

Naturland Fair combines fair trade criteria with Naturland's detailed standards for organic and sustainable production. It certifies producer groups in both the Global South and North but prioritizes partnerships with disadvantaged smallholders when products are available. Naturland Fair has specific environmental standards on energy use, agrobiodiversity, and GMOs. Its fair trade requirements related to pricing, premiums, and capacity building are good but do not fully match the most rigorous labels. Naturland Fair's standards development is guided by a democratic assembly of Naturland organic farmers.

This article explores the origins and history of chocolate, tracing cacao’s use and cultural significance among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. It

Embark on a journey through Taiwan’s lush Pingtung County, where 77-year-old Mr. Chou pioneers small-scale cacao farming, and award-winning chocolatier Jade Li transforms each harvest

Explore the delicious evolution of the best-selling chocolate bar, indulging in a rich history of flavor innovation and timeless satisfaction. Join us on a sweet journey through the irresistible transformation of the chocolate bar.

Keep up-to-date on upcoming chocolate awards