Best White Chocolate in the World

This article explores the origins and history of chocolate, tracing cacao’s use and cultural significance among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. It

News > Fair Trade Chocolate Labels Unwrapped and Explained

When the Spaniards initially arrived at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519, among the extravagant spectacles they saw was King Moctezuma being served over 50 jars of foaming chocolate. This drink, made from cacao tree seeds (Theobroma cacao), was the forerunner to what we now call chocolate. Chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who left behind the most extensive account of the Spanish conquest, noted that the Aztecs said the cacao beverage was for “success with women,” implying the connection between chocolate and romance is longstanding. Indeed, studies show a chemical found in chocolate, phenylethylamine, is the same one the brain discharges when someone experiences attraction.

However, for the Aztecs, the drink was far more than an aphrodisiac. Cacao was integral to their concept of political power and had a role in rituals of all kinds, including funerals and weddings. A 1545 document written in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and other Central Mexican peoples, shows cacao was even utilized as currency—a turkey cost 200 cacao seeds, a tamale was worth one seed, and a porter’s daily wage at the time was 100 seeds.

Despite its economic and cultural importance in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, archaeologists had only a hazy grasp of cacao’s history until recently. But in the past decade, analytical work on soiled clay pots by chemists at Hershey Company labs, the largest chocolate producer in the U.S., has pushed back the antiquity of cacao beverages by 2,000 years, to at least 1500 B.C., if not earlier. Understanding chocolate’s early history has led archaeologists to speculate that cacao played a pivotal role in the economic, religious, and political growth of peoples like the Olmec, Maya, and even the Anasazi, or Ancestral Puebloan peoples of the American Southwest.

Our international chocolate awards pay tribute to the obsessive, passionate individuals striving for chocolate perfection around the world. We honor renowned European chocolate houses who have perfected their bonbon and truffle recipes for generations alongside emerging bean-to-bar chocolate makers experimenting with bold ingredients like black currant and elderflower. During our blind tastings, we judge each craft chocolate bar and bonbon on its flavor, aroma, textures and craftsmanship to identify the best chocolate in the world.

See the winners +

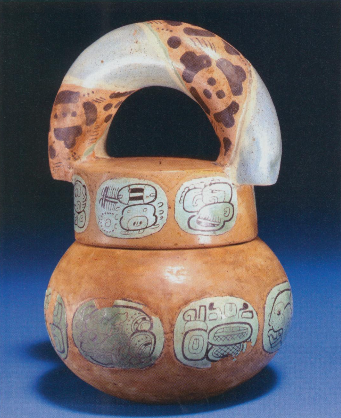

The search for chemical traces of ancient cacao began in 1984 in the northeast corner of Guatemala, when Harvard graduate student Grant Hall went into Tomb 19, a fifth-century A.D. chamber at the Maya site of Rio Azul, a city that at its peak housed 400,000. Adorned with vivid red murals, the royal tomb contained a male skeleton reclining on a fiber mattress surrounded by 14 vessels filled with provisions for the afterlife. Among the pots, one vessel particularly stood out to Hall. It had a locking lid, a thick curved handle decorated like a jaguar pelt, and was painted with turquoise patches covered in Mayan glyphs. Hall noticed a dark fill line inside and prudently scraped off some residue for later testing. Around the same time, University of Texas epigrapher David Stuart studied the Rio Azul pot’s 15 hieroglyphic panels and realized two contained a glyph he translated as kakaw—cacao. Now suspecting the residue might be from cacao, Hall wondered who could confirm or refute his hypothesis. On a hunch, he called Hershey’s toll-free number. His query reached a vice president, who contacted analytical chemist W. Jeffrey Hurst at the Hershey Center for Health and Nutrition in Pennsylvania. “They were seeking an expert in cocoa analysis,” recalls Hurst, whose lab has instruments that can identify chemical traces. “They could have called someone else, but I’m glad they called Hershey.”

Accustomed to developing new lab technologies and researching food safety, Hurst was intrigued by the unexpected extracurricular challenge. He began exploring hundreds of cacao compounds to select a promising proxy for the fruit that could be identified in ancient artifacts. The right compound had to reliably indicate cacao, be stable enough to survive centuries underground, and be abundant enough to detect from trace amounts. Hurst zeroed in on a chemical called theobromine as the best marker. It belongs to the same alkaloid class as caffeine, also found in cacao, though theobromine is ten times more plentiful. It occurs in at least 18 other plants, including coffee, tea, and kola nuts. But among Mesoamerican crops, only cacao has theobromine, so finding it in ancient pottery would signify the artifacts once contained cacao.

To identify theobromine, Hurst used some basic analytical chemistry tools. High-performance liquid chromatography separates compounds in a sample by their chemical differences. Mass spectrometry then pinpoints the specific compounds. The spectrometer records an unknown sample’s chemical profile, resembling an EKG heartbeat reading, which can be compared to standard profiles of known compounds. Using this technique, Hurst verified theobromine’s presence in the Rio Azul pot, making it, at the time, the earliest cacao use evidence: between A.D. 460 and 480.

Hurst got a second chance to test his cacao-detecting method in the mid-1990s. While excavating Belize’s remote Bats’ub Cave, University of New Mexico archaeologist Keith Prufer uncovered an adult male laid to rest behind limestone block walls sometime in the fourth or fifth century A.D. The man’s skull was removed and placed by his pelvis, and inverted over the pelvic bones was a crude pottery bowl covering five seeds. Where his head should have been was the bottom half of a ceramic vessel holding one jade bead. Despite being riddled with fungus, two burial seeds tested positive for theobromine in Hurst’s lab—rare intact ancient cacao examples. Prufer suggests the deceased was a shaman or similar, for whom the cacao signified elite status and ensured successful passage to the afterlife.

In 2001, the Rio Azul results also caught University of Texas graduate student Terry Powis’s attention. He was wondering why certain Pre-classic Maya spouted vessels were termed “chocolate pots” for nearly a century, when no one had determined if the teapot-shaped containers actually held chocolate. Powis worked in Belize at the Maya site of Colha, renowned for stone tool making, where several elite burials had these spouted pots. Using fine-grade sandpaper, he carefully scraped clay powder from 14 vessel insides, hoping to collect evaporated liquid traces. Powis sent the residues to Hurst, who says they resembled dirt more than chocolate. Nevertheless, in 2002 Hurst identified theobromine in three Colha pots, pushing back earliest cacao chemical evidence even further—around 1,000 years—to 600-400 B.C. The three positive pots were the only sampled ones archaeologists hadn’t cleaned post-excavation. So Powis, now at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, learned an important lesson: “If you really want to discover what people ate or drank, don’t wash anything.”

In recent years, growing archaeologist awareness of uncleaned pottery’s value has allowed Hurst to push the earliest known cacao beverage date back even more. Working in western Honduras’ Rio Ulua Valley, known in the sixteenth century for its high-quality cacao, archaeologists Rosemary Joyce of the University of California, Berkeley, and Cornell’s John Henderson have shown cacao beverages were consumed long before the Maya arose. In 2004, the two collaborated with Hurst and University of Pennsylvania molecular archaeologist Patrick McGovern to analyze pottery from Puerto Escondido, a small village first settled in the Early Preclassic Period (1800-1000 B.C.), when Mesoamericans were just starting permanent settlements, laying the foundation for subsequent complex cultures.

With no visible residues on the recovered pottery surfaces, the team used a destructive pulverizing process to identify theobromine trapped inside 13 sherds (archaeologists use the term “sherd” to refer to a fragment of a prehistoric or historic ceramic vessel, while the term “shard” refers to a fragment of glass). The selected sherds represented several vessel forms spanning a wide timeframe. In each case, Joyce and Henderson thought the shape or decoration suggested possible special beverage serving/drinking use, presumably cacao. Eleven proved correct. One bottle spout piece dating to at least 1150 B.C. and 10 slightly younger sherds had theobromine. Pottery from the earliest site history period is too rare to sacrifice for testing, but Joyce suspects cacao use there goes back even further, to around 1700 B.C.

The oldest Puerto Escondido pottery consists of elaborately decorated small bowls and flat-bottomed, neckless tecomate jars, which Joyce and Henderson believe may have been individual drinking vessels. Bigger bowls and tall, central spout bottles began appearing around 1400 B.C., indicating Puerto Escondido residents were no longer just consuming cacao drinks alone, but probably communally, perhaps during celebrations. Joyce notes cacao-positive pottery types appeared in households throughout, meaning there was enough to go around.

Early Preclassic cultures are thought to have been egalitarian, but Henderson and Joyce believe cacao parties could also signify some people—those with higher-quality polychrome pot access—were seeking greater status. “There were upwardly mobile communities using these distinct ceramics and chocolate to distinguish themselves,” Henderson states. “By hosting lavish cacao feasts, these people could have created social obligations that eventually engendered political power.”

Later Aztec and Maya lords utilized power over chocolate consumption to boost their status as influential elites with divine connections. But Henderson believes strategic early cacao use by a few could have laid the foundation for the Mesoamerican belief that select society members had the right to rule.

The Puerto Escondido team had another early cacao insight. While later cultures would ferment cacao seeds as the first nonalcoholic chocolate drink step, Joyce and Henderson believe Early Preclassic people were likely fermenting the sweet, creamy cacao pulp to make an alcoholic beverage similar to the 5% ABV chicha beer some Latin Americans still make from maize. Only later did Mesoamericans realize fermented seeds and pulp could form chocolate drink bases. Before fermentation, cacao seeds are unpalatable. “They’re like apple pits,” Joyce states. “Fermentation gives them the full chocolate taste.”

According to Joyce, chocolate was a fortuitous accident, a prehistoric brewing by-product. Soon after the 2007 Puerto Escondido announcement, Powis and colleagues reported even earlier cacao, from two Preclassic Mexican site potsherds—the Olmec’s El Manati village and Paso de la Amada, where the Mokaya built Mesoamerica’s earliest known ball court. Near Chiapas’ Pacific coast, Paso de la Amada also has the region’s earliest ceramics—thin-walled liquid servers. Hurst found a neckless tecomate jar sherd buried beneath the largest, most important structure’s floor contained theobromine. Made prior to 1500 B.C., it could date as far back as 1900 B.C., when the Mokaya first settled there. For now, Paso de la Amada has the earliest known cacao aficionados.

Hurst’s lab’s most recent discovery expands ancient cacao’s range not back in time, but far north, to the American Southwest. In the 1920s, Smithsonian archaeologist Neil Judd made a remarkable Pueblo Bonito discovery. This 800-room, multi-story Ancestral Puebloan village in New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon was first occupied in the ninth century A.D. While digging the older, northwest sector, Judd unearthed a compact, square room containing 111 tall, unique cylindrical jars. Fifty-five more have since emerged at Pueblo Bonito, but outside the complex, such vessels are practically unknown in the Southwest.

The geometric black-and-white decorated cylinder jars had long intrigued University of New Mexico archaeologist Patricia Crown. Noting their resemblance to some painted Maya vessels, Crown consulted Smithsonian Maya ceramics expert Dorie Reents-Budet, who said Maya glyphs indicated they held cacao beverages. “A light bulb went off, and I thought, ‘Wow, that would be really neat if they had cacao at Chaco,'” Crown recalls. Archaeologists already knew of Mesoamerican exchange since Mexican silver and macaw skeletons were found at Pueblo Bonito. “Part of why I thought cacao might have been in Chaco was the scarlet macaws,” Crown adds. “It would’ve been easier to bring cacao from Mexico than a squawking, sharp-beaked bird.”

Lacking written clues about the Chacoan vessels, Crown pursued cacao chemical traces. She had recently re-excavated Judd’s old Pueblo Bonito trash mound trenches, recovering over 200,000 artifacts. From these, Crown chose five sherds she believed were from cylinder jars or pitchers. No visible residue remained on the ceramics, but the unwashed sherds might have absorbed ancient contents. She finely ground each piece for Hurst’s analysis. The three most likely cylinder vessel samples tested positive for theobromine, and it having seeped into the clay implied they held a cacao beverage rather than intact seeds.

Cacao’s Pueblo Bonito appearance raises intriguing role questions. Tree-ring dating puts construction between A.D. 860-1128, with cylinders arriving post-1000 during monumental canyon construction, followed by swift societal decline. The cylinders’ Pueblo Bonito concentration may signify restricted production and consumption controls. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Crown and Hurst suggested “Pueblo Bonito’s growth, particularly obtaining Mesoamerican objects, cacao, and macaws, could have been coupled to some individuals acquiring esoteric Mesoamerican ritual knowledge.”

It’s tempting to speculate on a cacao bean’s Pueblo Bonito value, 1,200 miles from the nearest natural source. If one seed bought a tamale in sixteenth-century Mexico, where cacao abounded, how much purchasing power would it have had in the arid Southwest, where chocolate was an unimaginable luxury and power source?

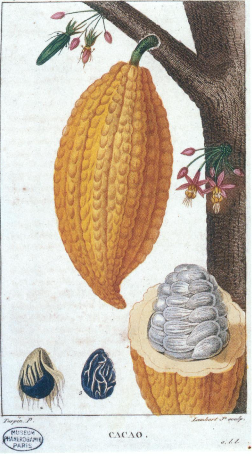

Hurst’s chemical detective work has dramatically reshaped our Mesoamerican chocolate beverage knowledge, but when or how cacao took root there remains a mystery. Many academics believe Theobroma cacao is an Amazonian native and was gradually introduced to Mesoamerica. Cacao trees don’t easily sprout from seeds, take years to mature, and only grow in humid lowland forest. In tropical climates, cacao pods quickly spoil, making transport via foot or canoe over long distances unlikely. With no evidence between the Amazon and Mesoamerica, University of British Columbia archaeologist Michael Blake speculates people moved cacao seedlings northward along the Andes through Colombia and Venezuela, planting as they went and awaiting yield.

Local cuisines probably prized cacao pods for fat or carbs before some proto-chocolatiers realized cacao also produced a tasty drink. Those unknown forest dwellers set in motion a process that hundreds or thousands of years later became a prime Mesoamerican cultural aspect, not to mention a modern industry generating over seven million annual tons of chocolate to satisfy global cravings.

The sacred Maya Popol Vuh text states gods created people from essential foods like cacao. In turn, people learned to create a delicacy fit for godlike kings from the cacao tree’s fruit, called Theobroma (Greek for “food of the gods”). Yet today’s sweet chocolate bears little resemblance to ancient Mesoamericans’ savory concoctions. Maya chocolate preparation required multiple steps. First, ripe cacao pods were harvested from forest/garden plots and cut open to remove seeds and surrounding pulpy flesh. (One pod holds enough beans for seven modern cups.) Letting beans germinate and ferment for days was key for chocolate’s familiar flavor. They were sun-dried for up to two weeks. Roasting over a flame imparted more taste and aroma. After husk removal, nibs were stone-ground into unsweetened dark chocolate-like paste. Other ingredients like maize, chilies, flowers, or vanilla enhanced flavor/medicinal properties. Adding water created a chocolate drink.

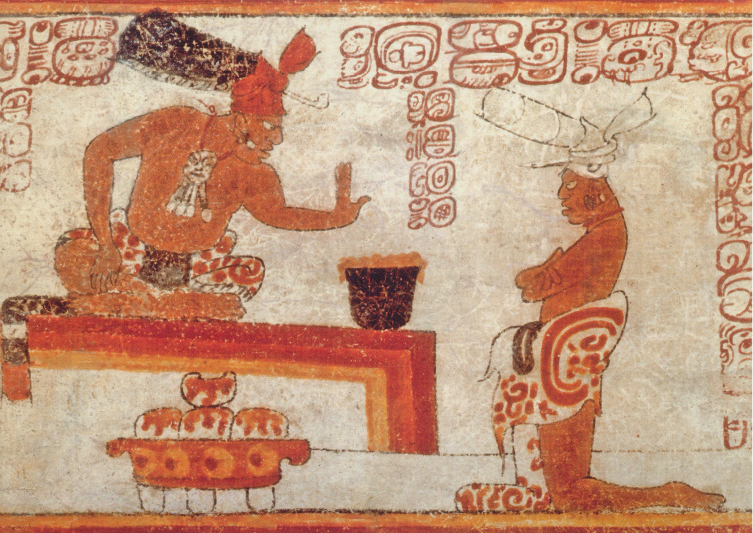

Like today’s cappuccino aficionados, elite Maya and Aztec prized chocolate foam. Froth improved aroma, taste, and perhaps had symbolic significance. Middle/Late Preclassic Maya stub-spouted vessels may have frothed liquid via blown air. In the Classic Period, foam production became a ritual involving pouring chocolate between decorated cylinders from on high.

This article explores the origins and history of chocolate, tracing cacao’s use and cultural significance among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. It

Embark on a journey through Taiwan’s lush Pingtung County, where 77-year-old Mr. Chou pioneers small-scale cacao farming, and award-winning chocolatier Jade Li transforms each harvest

Keep up-to-date on upcoming chocolate awards