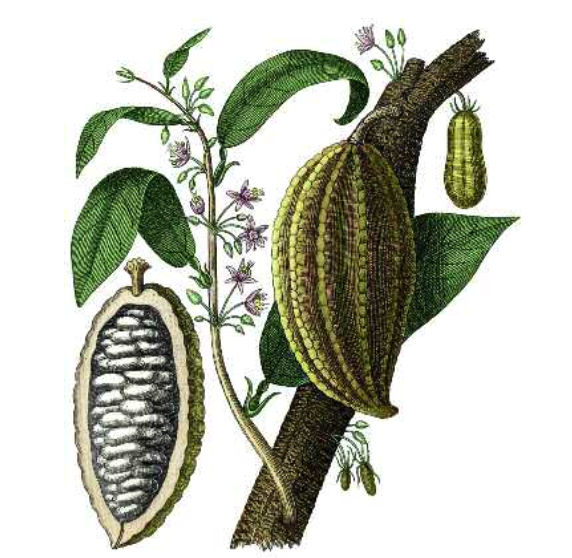

Chocolate is complicated. The “chocolate tree”, Theobroma cacao, grows only within twenty degrees of the equator, only below about 1,000 feet (300m) in altitude. It requires shade, which must be provided by taller trees, and humidity, and a temperature that remains above sixteen degrees Celsius, all of which mean that it does not grow within thousands of miles of the countries that consume the most chocolate.The tree does not take well to being farmed, and is prone to diseases which destroy entire plantations in a few weeks.

It depends on midges, which breed best on the floors of uncultivated rainforests, for pollination. The cocoa bean, a pod which grows out of the tree’s trunk, must be harvested with a carefully wielded machete to avoid damaging the buds from which more beans will grow, and the process of converting the resultant wrinkly pod into the shiny brown bars we eat is longer and more exact than any other in culinary history, involving a mixture of handwork and high technology which do not exist in the same economy and, ideally, time spent in at least two climates; the warm, damp environment where it grows and the arid heat required for drying. The chocolate we know is intrinsically modern, the product of a world divided between low-paid manual labor and mechanized food preparation, between hungry laborers and sleek consumers, and between the ecologically rich Equatorial nations and the economic powers of Europe and North America. It could not exist, in its familiar form, in any other era.

Mesoamerican Chocolate

In the beginning, there was no chocolate. There may have been wild Theobroma cacao trees in Central America before human beings reached that continent – there were, and are, other species of Theobroma – but in any case there is evidence that the tree was domesticated by the earliest civilization of the Americas. Sophie and Michael Coe argue in The True History of Chocolate that there is linguistic if not archaeological evidence linking Theobroma cacao with the Olmec, the people who inhabited the Mexican Gulf Coast between 1500 and 400 BCE. Partly because of the warm and humid climate which created the fertile lands on which this complex culture was based, little material evidence of Olmec life survives, but traces of cacao have since been found on ceramic vessels from Olmec-era, pre-Classic Maya sites in Belize. Descendants of the Olmec, the Izapan, are the most Cocoa harvest in West Africa – pods being opened with a small machete. Mayan stone with relief carving depicting the ruler Itzamna sitting on a throne holding a vision serpent. likely bearers of cacao to the Maya, whose magnificent cities were established in the cacao-growing lowlands by around. It is in the context of the Classic Maya civilization that we begin to encounter the origins of the modern myths of chocolate deployed on wrappers and in the more enthusiastic popular histories.

Both traces and images of Maya cacao consumption survive. Maya writing was decoded in the second half of the twentieth century, and although nearly all of the bark books and codices were destroyed either in the Maya Collapse of the ninth century, when the civilization entered a rapid decline, or by the Spanish in the years following the Conquest, hieroglyphs and pictures on vases attest to cacao use in the Classic era. Many of these vases were found in tests at the Hershey Laboratory in Pennsylvania to contain traces of the chemical theobromine, a component of chocolate that can survive for centuries. Four books survive from the post-Classic era, giving more detail about the first chocolate.

Maya vases depict the harvest, preparation and consumption of chocolate. The beans were picked, fermented and dried near the groves where they grew, after which they could be transported long distances, often up into the highlands, where consumption, at least among the rich, seems to have been untrammeled by distance from the raw material. (The distance between consumers and producers has been part of chocolate history from the beginning.) After that, women – it was always women – roasted the beans and then ground them with a pestle, a mano, on a flat mortar, a metate. A paste of cornmeal was often added at this stage, as well as spices, which might include vanilla, chili peppers and flower flavorings. The resulting paste was usually diluted to form a drink, which was taken hot or cold, but could also be made into thicker gruels or soups, or even dried to form cakes of ‘instant’ chocolate which could then be consumed while traveling. Before serving the drink, women would pour it from one container to another until a foam floated on the top.

Many of these vases have been found in graves, and there is usually evidence that they were left full of the prepared drink. The hieroglyphs on these ceramics dedicate the vessel to a god or patron, describe its shape, list the contents and end with a personal name, suggesting that the vases were commissioned by wealthy individuals in readiness for their own burials. Despite its high value, and possible use as a form of currency, cacao was not passed down families and therefore accompanied its owner on the final journey. The hieroglyphics suggest that cacao was involved in rituals for other rites of passage as well as burial, including weddings, anniversaries and celebratory or commemorative banquets.

It is easy to see how casual ideas about Mesoamerican history might claim therefore that chocolate was a magic or sacred substance, but we might first reflect on the role of alcohol in our own society: it is not magic, but widely regarded as pleasant and important in marking festivals and social events from ‘stag parties’ to Holy Communion.

A rival manufacturer advertised that his sweets could be found in every grocery store? No big deal. The rivals were counterattacked. Louit Hermanos & Cia. Chocolates, from Guipúzcoa, replied that their products “could be found in all good grocery stores.”

The Juncosa family (“For sale the main grocery stores and confectioneries in Spain”) also bragged about “using first class cocoa, sugars and cinnamon.” If others referred to people of “good taste,” the Juncosa family appealed to the class and elegance of its customers. In the politically drought era of Spanish politics, “class” had a special connotation. After the 1939 Spanish Civil War which saw the communists defeated by Franco’s fascist regime, the word class was always italicized or displayed in quotation marks to clarify the intended meaning.

Record number of gold awards for chocolate makers from everywhere

The newly awarded bars have seen a rise in the use of Indian cacao, notably from the Idukki region of Kerala, with its ideal cacao growing conditions. Read more +

Chocolate took on another function in Mesoamerica. It is often said that the Maya, and later the Aztecs, used cocoa beans as money, as a substitute for gold, and this analogy is presented as an antecedent to our own sense of chocolate’s powers. The discovery of fake cocoa beans from Balberta in the first centuries suggests a habit of counterfeiting which would only make sense if the beans were being exchanged for something of value (there is no point in counterfeiting something you are planning to cook), and certainly by the time the Spanish arrived at the Aztec court in 1521, cocoa beans were a recognized way of storing capital.

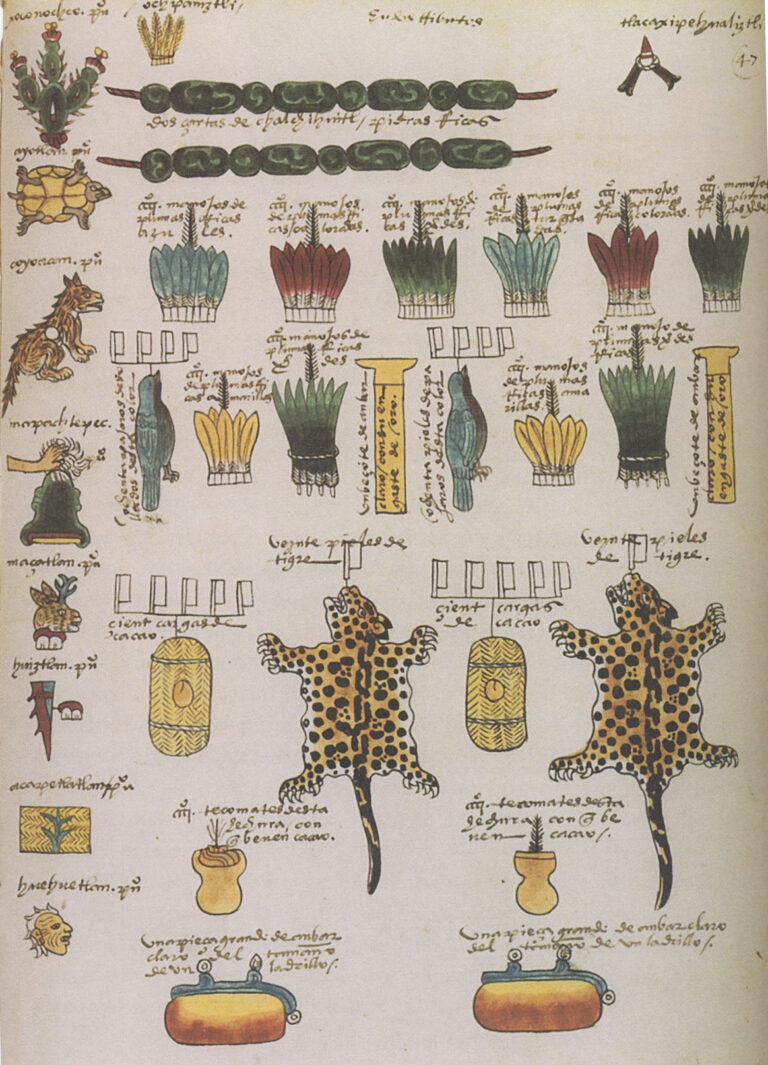

But these events are separated by fifteen hundred years, the distance between now and the decline of the Roman empire, and the meaning and function of the cocoa bean in Mesoamerica cannot have been stable or even consistent across those centuries. Cocoa beans and chocolate lent themselves to exchange because they were grown and produced in specific areas but consumed across the continent and were easily preserved and transported by cargo canoes and in tumplines, backpacks secured by a strap across the forehead. As the Aztec empire, based in what is now Mexico, drew strength after the final throes of the ‘Terminal Classic’ era of the Maya and the fall of the Toltec people who succeeded them, taxes and tributes were levied in the form of cacao. The Aztec infrastructure was rooted in networks for the passage and exchange of goods, and chocolate was the most portable and widely valued commodity of Mesoamerica.

No one is sure where the Aztec, or Mexica, people came from, but between the late fourteenth and late fifteenth centuries they established an empire based in Tenochtitlan, the site of the present-day Mexico City. The city throve on tributes exacted from subjugated provinces, and became the powerhouse of a complex and widely misunderstood culture.

Later Aztec rulers presided over courts whose hierarchies and etiquettes perhaps find a European equivalent in those of mid-eighteenth-century Versailles. The Aztecs practiced a polytheistic religion which was the basis for an advanced theology, and most of what we know and understand about these disciplines is based on, and thus inevitably shaped by, the accounts of the Spanish conquistadors and their henchmen. Some, especially the Franciscan missionaries of the mid-sixteenth century, learnt Nahuatl and devoted their lives to the study of Aztec culture, but even the most careful records by foreign ethnographers cannot be said, six hundred years later, to give any account of Aztec life that a citizen of pre-Conquest Tenochtitlan might have endorsed. What follows here is an account of the beginnings of European mythmaking about both chocolate and the cultures which originated it.

On August 15, 1502 Columbus had sent his men ashore at Guanaja, an island off modern Honduras, where they had arrived a few days earlier after a traumatic transatlantic passage. The original eyewitness accounts are lost, but Bartolomé de las Casas, working from these lost accounts, writes that, “as soon as the Governor had gone ashore at this island . . . a canoe full of Indians arrived, as long as a galley and eight feet broad; it came loaded with goods from the west.” These goods included, “wooden swords . . . certain flint knives, small copper hatchets, and bells and some medals, crucibles to melt the copper; many cacao nuts which they use for money in New Spain, and in Yucatan, and in other parts.”

Since these travelers “did not dare defend themselves nor flee seeing the ships of the Christians”, they were taken to the Admiral, who offered gold in exchange for information about local resources. It is Columbus’s son Ferdinand who provides the often-quoted detail that this Maya trading canoe was stocked with “those almonds which in New Spain are used for money. They seemed to hold these almonds at great price; for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen.” This is where the equation between chocolate and gold enters the European imagination.

Both Ferdinand Columbus’s and Bartolomé de las Casas’s accounts of this encounter help to inaugurate the trope in which the ‘primitive’ people place exaggerated value on something which is, to the eyes of the ‘civilized’ observer, obviously ephemeral. The people who use nuts as money or value them as if they were eyes anticipate Captain Cook’s account of Tahitian excitement over red feathers, or early European accounts of the Native American use of beads.

Cacao here is merely a strange plant apparently inscribed with excessive value by people who have not yet encountered the real thing, money. Europeans begin to develop a mythology for it. On this day Guanaja, also known variously at this date as Bonaca and the Island of Pines (Columbus’s name for it), began its journey from habitat to source of a luxury comestible. Columbus turned round in search of gold, leaving those who traveled in his wake to discover what those beans were for.

It is no coincidence that the “most powerful” of the luxury French chocolate manufacturer Valrhona’s Grand Cru chocolates, characterized by “an exceptional bitterness”, is called Guanaja. Valrhona state, ambiguously, that Guanaja was “the first to delight lovers of bitter dark chocolate”, leaving us to guess whether this refers to early consumers of the Valrhona bar or those first European visitors to the island. In the pile-up of adjectives that typifies descriptions of fine chocolate in the twenty-first century, Guanaja’s “intense taste brought out by hints of flowers reveals intensity – exceptionally long on the palate.” The consequences of a fleeting encounter on Guanaja that day might well leave a bitter taste.

There were only two years between the first Spanish encounter with the Aztecs in 1519 and the sacking of Tenochtitlan, so what we know about the Aztecs is to a large but indeterminable extent what we know about the Conquistadors. The civilization, including its libraries, was systematically destroyed before any real understanding could have been achieved. But the evidence suggests that great wealth was partnered with sumptuary laws, familiar to medieval Europe, which placed stringent restrictions on luxury even for the upper echelons of a highly stratified society, and that the conspicuous consumption of the court of Moctezuma II was balanced by the ascetic lives of the middle classes. As this suggests, the earliest observers report an ethic of austerity in Aztec society that has been erased from later accounts of debauchery and bloodletting. Chocolate was reserved for those who made the greatest sacrifices to the state, and even then was taken in small quantities at the end of a banquet.

There is relatively little evidence for the association between chocolate and blood. A passage in the Franciscan ethnographer Bernardino de Sahagún’s account of Aztec religious ritual, quoted in most histories, suggests that a drink made from cacao and blood-stained water was given to sustain the spirits of sacrificial victims through their final dance, and there was some literary connection between the cocoa bean (which is indeed heart-shaped) and the human heart. One of the traditional ingredients of the chocolate drink, annatto, is also a red food coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote shrub, but it was the Spanish historian and writer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés who made the connection between the stained lips of those who had partaken and fresh blood. Again, it is impossible to separate the tensions surrounding first encounters from the cultural peculiarities of cacao in Aztec society, but some of our own ideas about chocolate’s powers and significance are clearly rooted in these earliest anxieties of empire.

More News

Best White Chocolate in the World

This article explores the origins and history of chocolate, tracing cacao’s use and cultural significance among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. It

Taiwan’s Pioneering Cacao Farmers of Pingtung County

Embark on a journey through Taiwan’s lush Pingtung County, where 77-year-old Mr. Chou pioneers small-scale cacao farming, and award-winning chocolatier Jade Li transforms each harvest

A Century of Sweet Success: The Evolution of the Best-Selling Chocolate Bar

Explore the delicious evolution of the best-selling chocolate bar, indulging in a rich history of flavor innovation and timeless satisfaction. Join us on a sweet journey through the irresistible transformation of the chocolate bar.

Don’t miss out on the latest Craft Chocolate news

Keep up-to-date on upcoming chocolate awards